How FreshBooks scales Capybara testing

An unfortunate truth is that for many web applications the best way of doing a comprehensive automated integration test is via tools like Capybara. This is the story of how FreshBooks scaled our Capybara testing infrastructure so that developers can depend on the tests being both reliable and fast.

Capybara provides an abstraction layer on top of runners such as Selenium and Webkit drivers. It allows developers and QA to write tests in human-friendly language like the following:

Feature: User signup

As a user

I want to sign in

Background:

Given user with "minichate@gmail.com" email and "1qaz2wsx" password

Scenario: Signing in with correct credentials

When I go to sign in page

And I fill in "email" with "minichate@gmail.com"

And I fill in "password" with "1qaz2wsx"

And I click "Login" button

Then I should see "Welcome!"However, traditionally running Capybara tests have been extremely slow. For one application at FreshBooks that has several hundred scenarios accross dozens of feature files it’d take hours for a machine to actually complete all the tests.

A short history of Capybara at FreshBooks

Our original implementation had a single machine running the Capybara tests against a fairly beefy “Release Candidate” environment. This environment had the latest stable versions of backend webservices running on it, to which we deployed the version of the application we wanted to run our Capybara suite against.

The tests themselves were run using parallel_tests which splits the tests into multiple groups and runs each of those groups in their own process.

There were many problems with this process, most notably that:

- The version we wanted to test (ie: we don’t yet know if its any good!) needed to land on our RC environment before we could test it

parallel_testsruns seperate processes, and so memory usage on the test runner machine went through the roof. We’re using PhantomJS as the “browser”, and regularly saw the entire host machine’s memory being consumed by 4 or 5 phantom processes.- The tests just weren’t returning reliable results. Whether it was resource constraints on the RC environment, or memory pressure on the test runner it seemed as if we were constantly chasing the next bottleneck. Meanwhile, developers learned to not trust the test results; not exactly and ideal situation

Something needed to change. Not only were the results training developers to not want to add more tests (flakey ad-inifinitum :( ) they were taking way too long to complete. We’d merge “trival” fixes into the release branch before getting a passing build, only to discover later that we’d subtly broken a feature.

“It was just a CSS refactoring. You don’t need to test it. What could possibly go wrong?”

– Anandh (Developer at FreshBooks)

Truely parallel testing

The fix of course is to parallelize every aspect of the test runner, not just the number of processes competing for the same underlying resources. The details of our implementation are a little specific to our technology stack, but I’ll detail them here regardless.

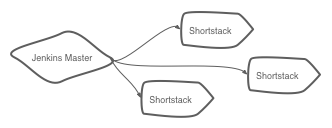

We have a project at FreshBooks we call Shortstacks which configures a machine to behave like a little mini-FreshBooks. All of our applications and storage services run on the machine, completely isolated from outside dependencies.

How we do this isn’t important (Docker!); the important detail is that we can treat each machine as an identical environment and run a subset of tests against it, then roll up the results of those tests for display to developers.

Jenkins Configuration

We use Jenkins as our CI tool, along with a forked version of the Jenkins Amazon EC2 plugin to provide an effectively unlimited number of build workers. The build workers scale with demand; if there are builds waiting in the queue, the plugin will provision additional workers.

With the capacity problem solved, we next turned to figuring out how to split the tests across multiple jobs.

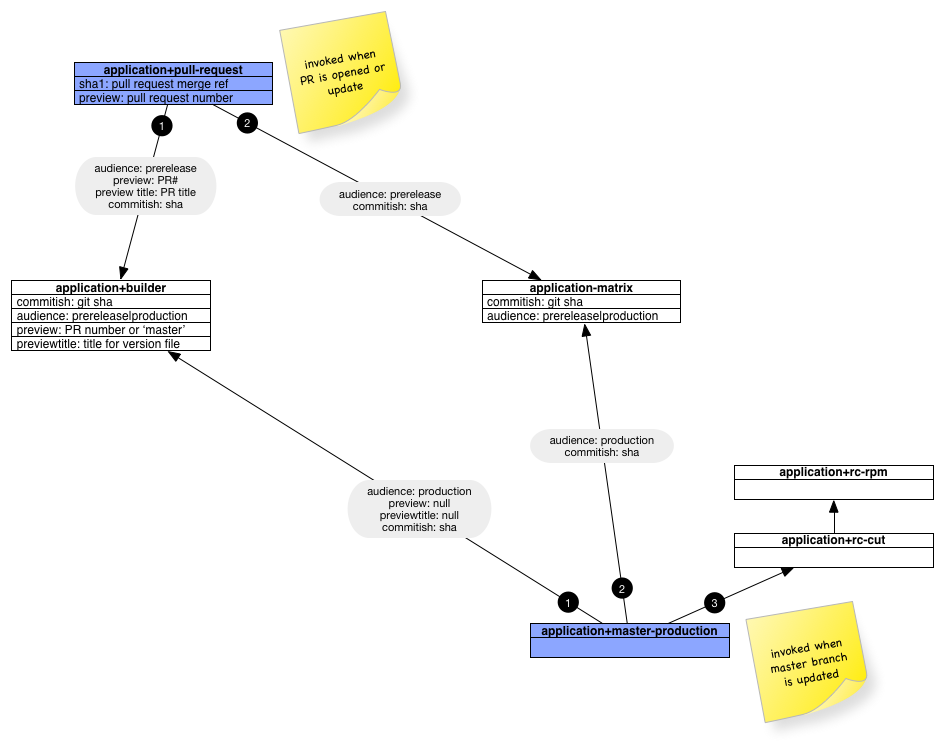

How we actually configure and lay out the Jenkins jobs is probably worth discussing; they look like:

application+pull-request

The application+pull-request job kicks off automatically whenever a Pull Request is opened or updated. It doesn’t do any real work itself, its simply a co-ordination job.

It is configured to watch the main application repo. We handle this by configuring Jenkins to watch the +refs/pull/*/merge:refs/remotes/origin/pr/*/merge refspec.

This lets us build against the merge commit representing a Pull Request’s HEAD and the HEAD of origin/master. This ensures that we’re running against a configuration that represents what a developer could expect to see if they actually merged their branch now.

The only task job does is to write out a .properties file that we can pass to subsequent build steps as parameters:

sha=$(git show ${sha1} | sed -n '/^commit / s/commit //p')

cat <<EOF > build.properties

commitish: ${sha}

audience: prerelease

preview: ${ghprbPullId}

previewtitle: ${ghprbPullTitle}

EOFWe then kick of the next two jobs serially with the parameters above; application+builder and application+capybara-matrix and block until they return results.

application+builder

In this job we build a Docker image representing the code at the HEAD of the merge commit. Again, we use Docker for this, but you can use your existing artifacting system.

It is configured to watch the main application repo. We handle this by configuring Jenkins to watch the +refs/pull/*/merge:refs/remotes/origin/pr/*/merge refspec.

We also run unit tests in here, which I don’t love. Someday soon I think we’ll investigate moving this into a seperate non-blocking job to speed up the overall build.

Assuming tests and artifacting are successful, we mark the build as SUCCESS, returning control back to the parent application+pull-request job.

application+capybara-matrix

This job is different than the above two jobs, in that we don’t have the job configured to watch the application repo. Instead, the job tracks our shortstacks repo, which is a set of Ansible playbooks. The key point here is that since we already have a set of assets built by the previous application+builder job we don’t need them here. Details about how we use the shortstacks roles are detailed later on.

We decided to use a Matrix job with a bit of Groovy to split up the tests by .feature file:

repo = "https://github.com/freshbooks/application.git"

workdir = "/var/lib/jenkins/workspace/application"

def version = 'origin/master'

if (context != null) {

def resolver = context.build.buildVariableResolver

version = resolver.resolve("commitish")

}

if (version == '') {

system.exit(120)

}

("mkdir -p "+workdir).execute()

("git clone "+repo+" "+workdir).execute()

("git fetch --all").execute(null, new File(workdir))

("git checkout --force "+version).execute(null, new File(workdir))

def command = [ "git", "ls-files", version, "features/" ]

def proc = command.execute(null, new File(workdir))

proc.waitFor()

def result = []

proc.text.eachLine {

if (it.endsWith('.feature') && !it. contains("prod_smoke")) {

def feat = it.replaceAll('/', { return '__' }).replaceAll('features__', { return '' }).replaceAll('.feature', { return '' })

result += feat

}

}

def groups = []

result.collate(4).each {

groups += it.join(' ')

}

return groupsYou can probably tell we’re not exactly professional Groovy developers, but the above works for us. Basically, we clone the application from GitHub at the start of the run, defaulting to the origin/master branch, unless otherwise requested via the commitish parameter. We then build up a list of relevant .feature files and collate them into groups of 4 tests per permutation.

For those unfamilar with Matrix jobs in Jenkins, the “splitter” above simply provides the matrix permutations (or “sub-jobs”) with parameters on what configuration they should execute with.

The two axes are:

- a space seperated list of feature files generated by the test splitter above, and;

- a label representing a set of EC2 workers that the jobs can run on

Now that we have the axes configured we can configure the actual matrix sub-jobs themselves.

We do something like:

- Run

ansible-playbooklocally on the node, given the fact that Jenkins has helpfully checked out the source for us via the Git configuration detailed above - Run the Docker

applicationimage represented by the SHA passed in via thecommitishparameter. This gets us the version of the application built in theapplication+builderjob. - Run the tests!

The actual test runs are triggered by something like:

for FILE in $FEATURE; do

FEATURE_PATH="features/"$(echo ${FILE} | sed 's/__/\//g')".feature"

NAME="capy-${FEATURE_PATH//\//-}-${BUILD_NUMBER}"

CMD="docker run --rm -t --name ${NAME} -v ${WORKSPACE}/tmp/run-${FILE}:/tmp -v /dev/log:/dev/log freshcloud/application:phantom.${commitish} bundle exec cucumber -p ${audience} -p screenshots -p debug --tags ~@skip --tags ~@flakey --tags ~@search -f json --expand -o /tmp/report.json ${FEATURE_PATH}"

echo "running ${FEATURE_PATH}"

mkdir -p tmp/run-${FILE}

$CMD > tmp/run-${FILE}/stdout &

sleep 3

done

echo "waiting for jobs to wrap up"

waitIn short, we’ll start a set of Docker images in parallel which actually run the Capybara tests against the local shortstack instance.

We don’t bother using parallel_tests anymore, since Bash itself has sufficient parallelization control for our needs; previously we had an unbounded number of .feature files that might need running, but now we know that we have a finite number of them that will be passed in via the test splitter (see the Groovy code above).

Conclusion

We’ve found that not only is this scheme far more reliable than the previous iteration of our Capybara infrastructure, but it tends to keep the actual total time for a test run down to a constant number of minutes. As the number of .feature files grows we’ll automagically provision more EC2 test infrastructure to handle the additional load.

Whereas previous test suite runs used to take hours or more to complete, the new infrastructure takes around 13 minutes from start to finish, allowing very fast feedback to Developers and helping them iterate faster.

13 minutes seems pretty good from where we stood several months ago, but is in fact almost 3 times longer than our goal. Hopefully I’ll be able to detail how we’re going to optimize the total run time down to our target of 5 minutes in a later post!

I suppose I should also mention that if you’re interesting in helping build some world-class testing infrastructure, you might want to join FreshBooks!